Salt Brine Vs Beer for Beef

Each method has its place

The origin of brining is lost in the mists of history. Did a lone African shepherd discover an antelope carcass on the coast, drenched in salt water, and then deem it amazingly tasty when cooked? Or did a sub-Saharan nomadic tribe stumble upon a camel on the Kalahari salt flats, its flesh embedded in the dry salt beds, and find it to be deliciously moist when roasted over the fire?

We will probably never know the truth. Yet we continue to brine food today because it makes food juicy and flavorful. Still, the modern fire-loving tribe yearns for an answer to the age-old question: Which is best, wet brining or dry brining?

To find out, our intrepid science advisor, Dr. Greg Blonder, experimented with two meats: lean chicken breast cooked hot and fast and beef brisket smoked low and slow. Both meats were wet brined and dry brined. Along with Blonder's previous experiments, these test results showed that wet brines work best for some meats, while dry brines win the day for others. Sorry, folks. There's no once-and-done answer here. But we can share some clear guidelines about which foods to wet brine and which ones to dry brine. If you want a primer on brining in general, what it does, how it works, and how to do it, check out our articles on Salt and Brining and Dry Brining.

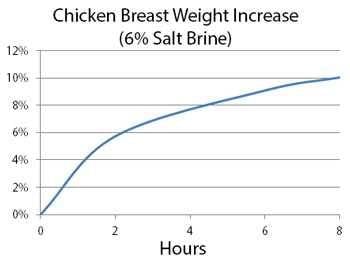

Meanwhile, back at the lab…Dr. Blonder's chicken breast experiment probably gave us the clearest conclusions. He wet-brined a half-pound boneless, skinless breast in 6% brine, which created a 1.5% salt level inside the meat over an 8-hour brining period. He also dry brined a chicken breast at the same level of 1.5% salt, which is waaaay too much surface salt for eating, but a good amount to illustrate the results of different brining methods after cooking.

One of the most important findings: the wet-brined chicken absorbed some water from the brine and increased its raw weight by 10%.

Both the wet-brined and dry-brined breasts were then cooked in a 325ºF oven alongside an unbrined control. You might think that that the wet-brined chicken would take longer to cook because it weighed more, but all three chicken breasts cooked at the same rate, which you can see in the chart below.

All of the chicken was removed from the oven when it hit 160ºF internal temp, and it was after cooking that the real benefits of brining the chicken showed up. As a percentage of the original raw weight, the wet-brined chicken lost nearly half the weight that the plain chicken lost! In other words, some of the absorbed water remained in the cooked, wet-brined meat—7% to be exact.

| Chicken Breast | % Cooked Weight Loss | % Raw Weight Loss |

| Plain | 15% | 15% |

| Dry Brined | 12% | 12% |

| Wet Brined | 16% | 8% |

The retained water in the cooked chicken helped to make the wet-brined meat taste slightly juicier. But even the dry-brined chicken lost less water weight than the unbrined control. As Dr. Blonder explains, salt ions act like electrostatic glue, preventing moisture from easily leaving the meat.

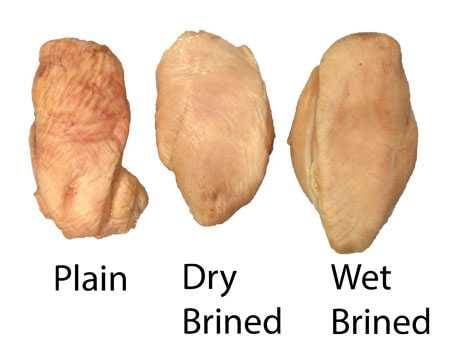

Bottom line: both wet- and dry-brining helps lean chicken breasts hang onto water, but wet brining helps a bit more. That's good news because grilled chicken is notoriously dry. Brining can help! You can actually see the difference brining makes in Blonder's photos of all three chicken breasts after cooking:

The plain breast was shriveled and less tender compared to both dry- and wet-brined breasts. It was nothing you would really want to serve to your guests.

In this experiment, the only downside to wet brining was that the extra water diluted the "chickeny" taste of the wet-brined chicken, a slight trade-off for keeping it nice and juicy.

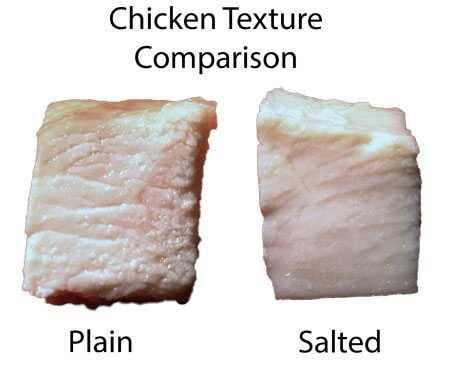

Apart from juiciness, Dr. Blonder's brined chicken experiment illustrated another interesting effect of brining in general: it can create a sort of meat polymer. Here's what happens: High concentrations of salt cause meat proteins to break apart, and the dangling ends of protein are then free to bond with other dangling ends of protein and to water, forming a kind of meat gel or polymer. This is exactly why we recommend salting only the exterior of burgers and meatballs—and not the interior. If you salt the whole ground meat mixture, you increase your chances of cooking up tough hockey pucks and baseballs instead of tender burgers and meatballs. Nobody likes to eat tough pucks and baseballs—not during the game and definitely not at the table. Want to see this polymerized meat texture yourself? Check out the cut samples of plain and brined chicken below:

Blonder explains that the muscle structure of the brined chicken gets rearranged by the salt, and re-bonded into a more homogeneous mass. So, at what level does meat become fully plasticized? Around 1.5% to 2%, according to Blonder. Which is much too salty to eat, thankfully. For brining, our target level of salt is only 0.5%, an amount that adds a nice bump in flavor while hanging onto moisture.

Nonetheless, with either brining method, the salt level on the very surface of the meat will exceed 2%. In dry-brined meat, the surface is at 100% salt under each salt crystal, and in wet-brined meat, the surface is at 6% everywhere. That high surface level of salt and the resulting meat polymer can affect other important food characteristics, such as the crust on your meat, or more importantly, the bark of your brisket.

And that brings us to Blonder's brisket experiment. As you'll see, dry brining a brisket partially polymerizes the surface and helps create a nice, thick bark. That's the good news. The bad news: that dry surface also inhibits smoke absorption. Curse you, Barbecue Gods! As for the wet method, Dr. Blonder's experiments show that wet brining does not help brisket retain any more moisture after cooking. It's the exact opposite of the wet-brined chicken, which did stay moister after cooking. Here's a closer look.

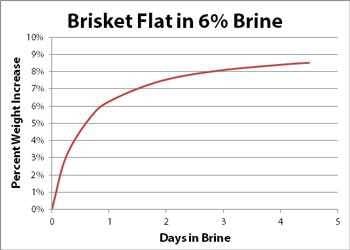

Blonder soaked a beef brisket in 6% salt brine—the same percentage as the chicken—and after 4 days, it absorbed around 9% in water weight, similar to the 10% increase in the wet-brined chicken. After a few days soak, the 6% wet brine also gave the brisket the ideal concentration of 0.5% salt inside.

For the dry-brine, Blonder rubbed another brisket with a 1% salt rub and let it sit for two days. As with the dry-brined chicken, this is a higher level of surface salt than normal, but it accentuates the differences in cooking both types of brined meats. After brining, both wet and dry briskets were cooked in the oven at 225ºF until they reached an internal temperature of 203ºF.

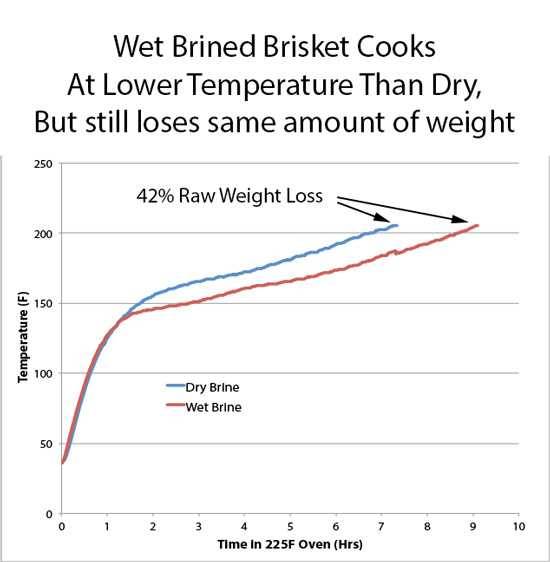

Was the wet-brined brisket juicier? Nope. It turns out that the long cooking time eventually forced the same amount of water out of the brisket no matter how it was brined. Both brined briskets weighed exactly the same when removed from the oven—even though the wet-brined brisket started out 9% heavier. And, in a blind taste test, both were equally tender and moist. The only difference was that it took the wet-brined brisket longer to cook.

So what caused the wet-brined brisket's longer cook time? The extra water! More water means more evaporative cooling, which is a general phenomenon of cooking that's super-important to understand. Evaporative cooling is the root cause of the infamous and annoying stall, the bane of every pitmaster's existence. Basically, the wet-brined brisket was sweating out its 9% extra moisture, which cooled down the surface of the meat just like the sweat on your skin cools you down on a hot day. That extra moisture—and the evaporative cooling it caused—made the wet-brined brisket take about 2 more hours to reach its doneness temp.

The upshot: there's no moisture benefit to wet-brined brisket. And the downside: there's a time penalty.

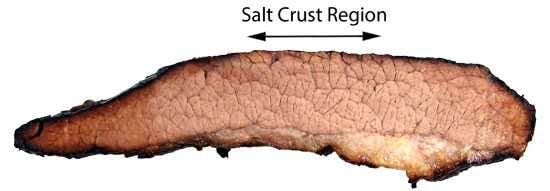

What's more, Blonder found that wet-brining brisket inhibits bark formation. The wet-brined brisket exuded so much moisture during cooking that the surface never fully browned. The extra moisture prevented a crisp bark from forming until the very end, after the water had finally evaporated. The wet-brined brisket actually stayed gray in color throughout the cooking until the very last hour. The dry-brined brisket, on the other hand, developed a thick, mahogany colored bark.

So which method wins for brisket? Based on these results, dry brining wins hands down. And that's the opposite of what works best for chicken breast.

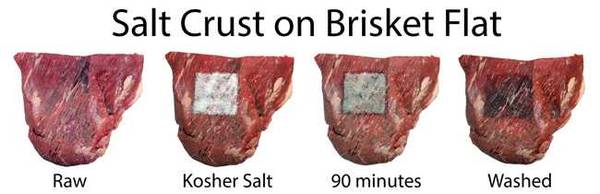

So dry brine your brisket for the best results, right? If only it were that easy! Dr. Blonder also found that dry brining brisket makes it take on less smoke. D'oh! That's not what we want from barbecued brisket! Remember how the brined chicken formed a sort of meat polymer? Well, the same thing happens with beef. To illustrate, Blonder coated a small square section of brisket with a crust of nothing but kosher salt. (As long as you wash the salt off after 90 minutes, the total amount of absorbed salt still averages under 0.5%, so this is a quick and viable dry brining method). Look at how the salted square of meat turns deep red in this photo sequence, just as if it were being corned for corned beef:

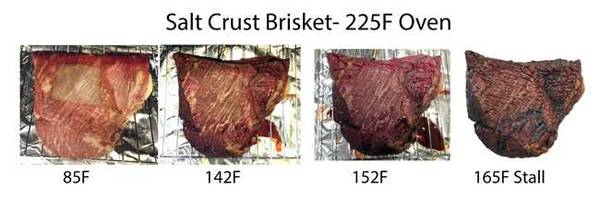

When cooked in an oven, the salted areas browned almost immediately. That's because, as Blonder explains, all of the protein bonds broken down by the salt were more available for Maillard (browning) reactions. Even when the brisket was well into the stall at 165ºF internal temperature, a remnant of the salted square area was still visible:

To see how that dry-brined square of meat responded to smoke absorption, Blonder repeated this salt crust experiment in an electric smoker, which produces a lot of smoke. The smoker test showed that the salted meat square took on less smoke because it became dry and polymerized (see the photo below). Which makes total sense because we know that smoke sticks best to water. This means that dry brining a brisket can ultimately make it less smoky tasting.

So let us get this straight: dry brining enhances browning and bark formation, but it inhibits smoke absorption? What's a poor pitmaster to do? What is the best way to reach the Holy Grail—a smoky, juicy brisket with a thick bark?

Don't worry, not all is lost. First, Blonder recommends using coarse or kosher salt in your dry brine or dry rub. The coarseness of the salt limits the areas of high salt concentration, reducing the total area of dry, polymerized meat on your brisket. That means more of the meat's surface can still absorb smoke. Second, you can help your dry-brined brisket take on more smoke by keeping your cooking environment moist. For that, we recommend a water pan. A humid cooking environment helps more smoke adhere to the meat's surface.

Whew—that was a lot to learn! What have we gleaned from the good doctor's experiments? The bottom line is that wet brining tends to work best for relatively lean meats like chicken breasts, turkey breasts, pork loin, and fish. In general, wet brine delicate foods that cook pretty quickly. For everything else, including most tough meats and roasts that take longer to cook, dry brining is the way to go. The one exception: skin-on poultry. There's always an exception! For skin-on poultry—including smaller parts—stick with dry brines, which help to crisp up the skin. Wet brines just make poultry skin soggy, and that's a sorry sight on any plate.

Source: https://amazingribs.com/wet-brining-vs-dry-brining/

0 Response to "Salt Brine Vs Beer for Beef"

Post a Comment